August 2023

In this age of deep or hyper imaging when satellites and drones have mapped the earth down to the last square metre one would be forgiven for thinking a field survey is old-fashioned and passé. But as every researcher knows that is not the case. Satellite mapping, while invaluable for questions at large spatial scales, doesn’t work when we want to know what’s happening at the village or even mohalla level.

The kind of information that you gain from the simple act of walking and observing your field site is not possible when looking at pixels on a screen, however rich in spatial and spectral information. Knowledge about your field site has to seep into your brain from your senses – sights, sounds, smells – and even thoughts and emotions evoked in the field. New questions arise in your mind as you walk around and certain causal relationships become clearer the more you visit places that you thought were familiar. Chance encounters with people from the area who provide their own stories about changes they see happening. All these add up to give you a richer picture of the field, one that isn’t just a factual record of changes but contains micro-level details that can allow for a richer and more layered understanding of the processes happening at your field site.

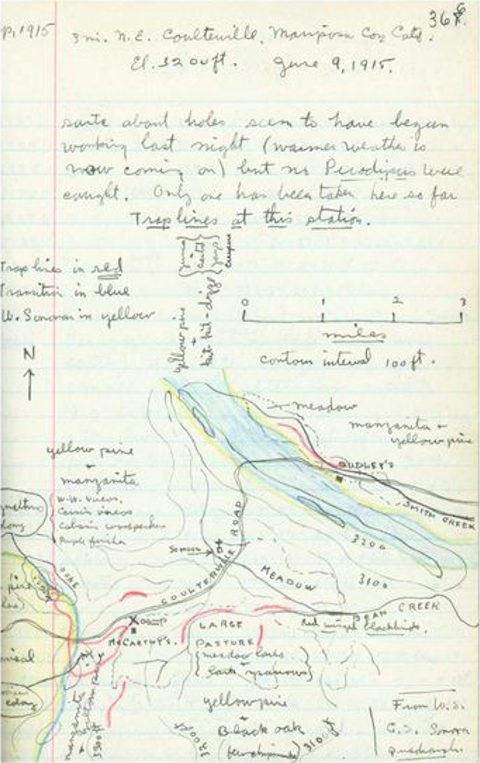

In the image below an example of field notes are shown that were made over 100 years ago. Joseph Grinnell, an American ecologist standardized the format for field notes collected by his team in their efforts to document the flora and fauna of California. One sees immediately the level of detail provided in these notes, details that have been gathered by painstakingly walking through the field site, perhaps multiple times.

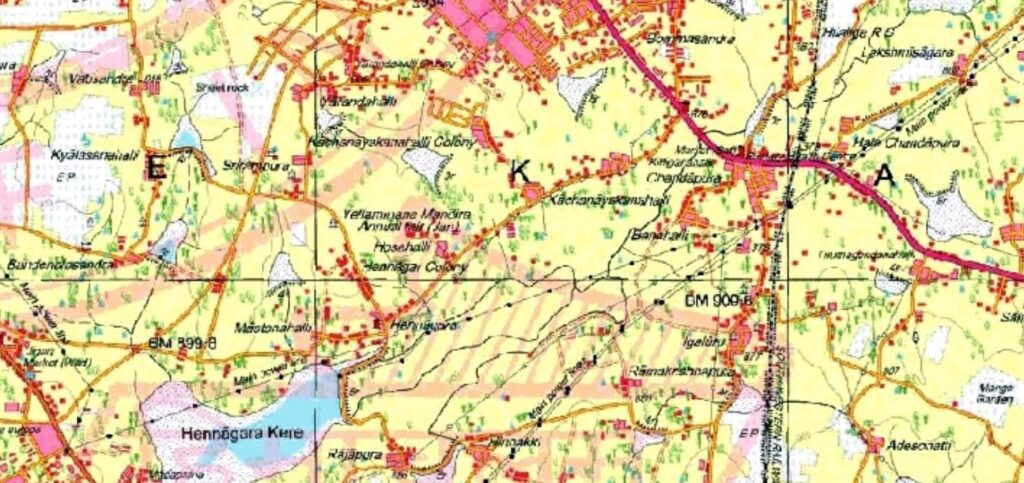

Survey of India topographic maps do something similar. They provide detailed information of natural and cultural features such as relief, vegetation, water bodies, cultivated land, settlements, and transportation networks (taken from NCERT). Since the geographic position and elevations of all these features, natural and man-made, are marked, it is easy to use these maps for travel, surveys and research. Again, these maps are produced by walking and taking coordinates and elevations in a particular location and repeating the procedure over and over again. While we don’t strive for this level of detail on our tank surveys, it is good to keep both these examples in mind.

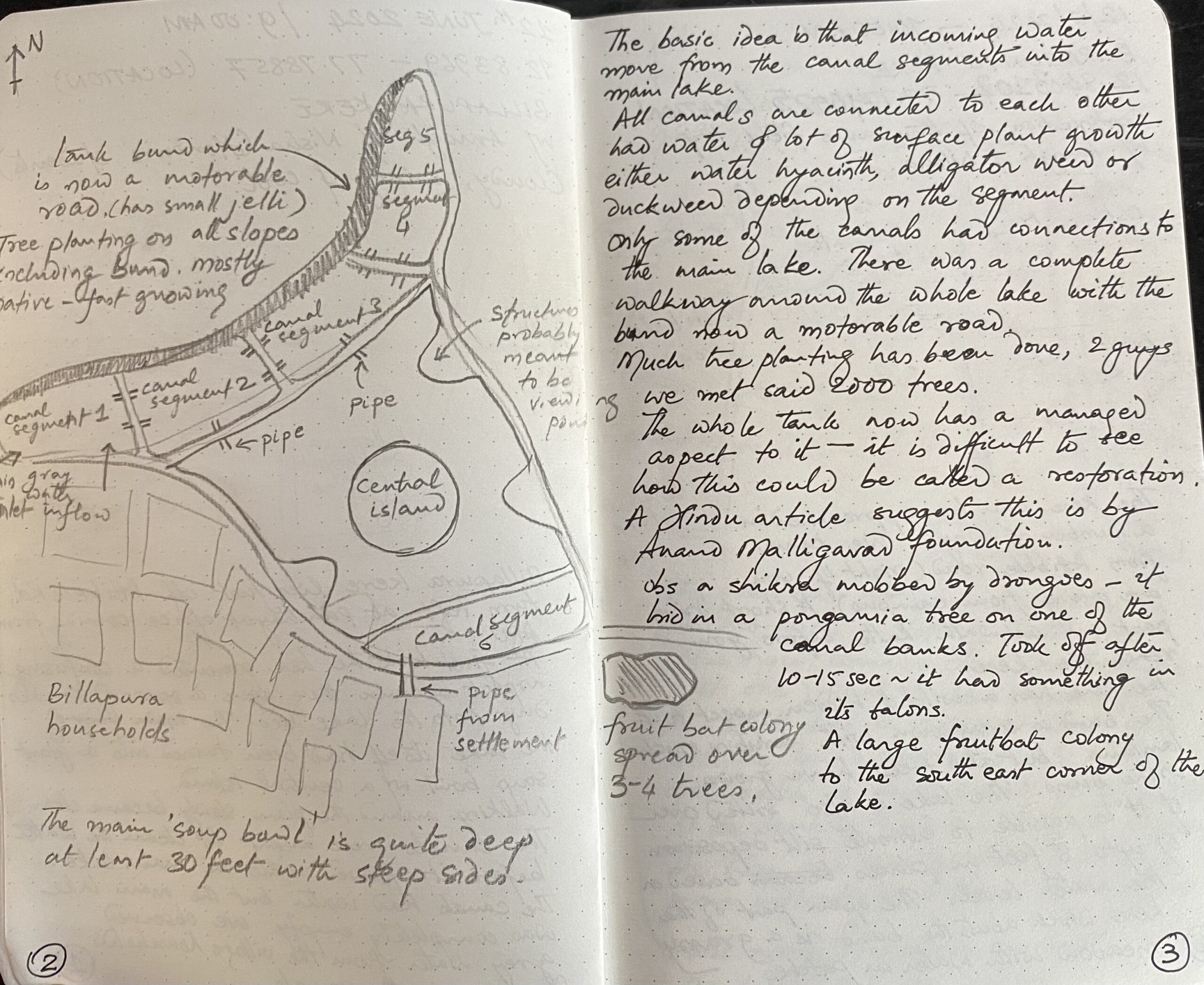

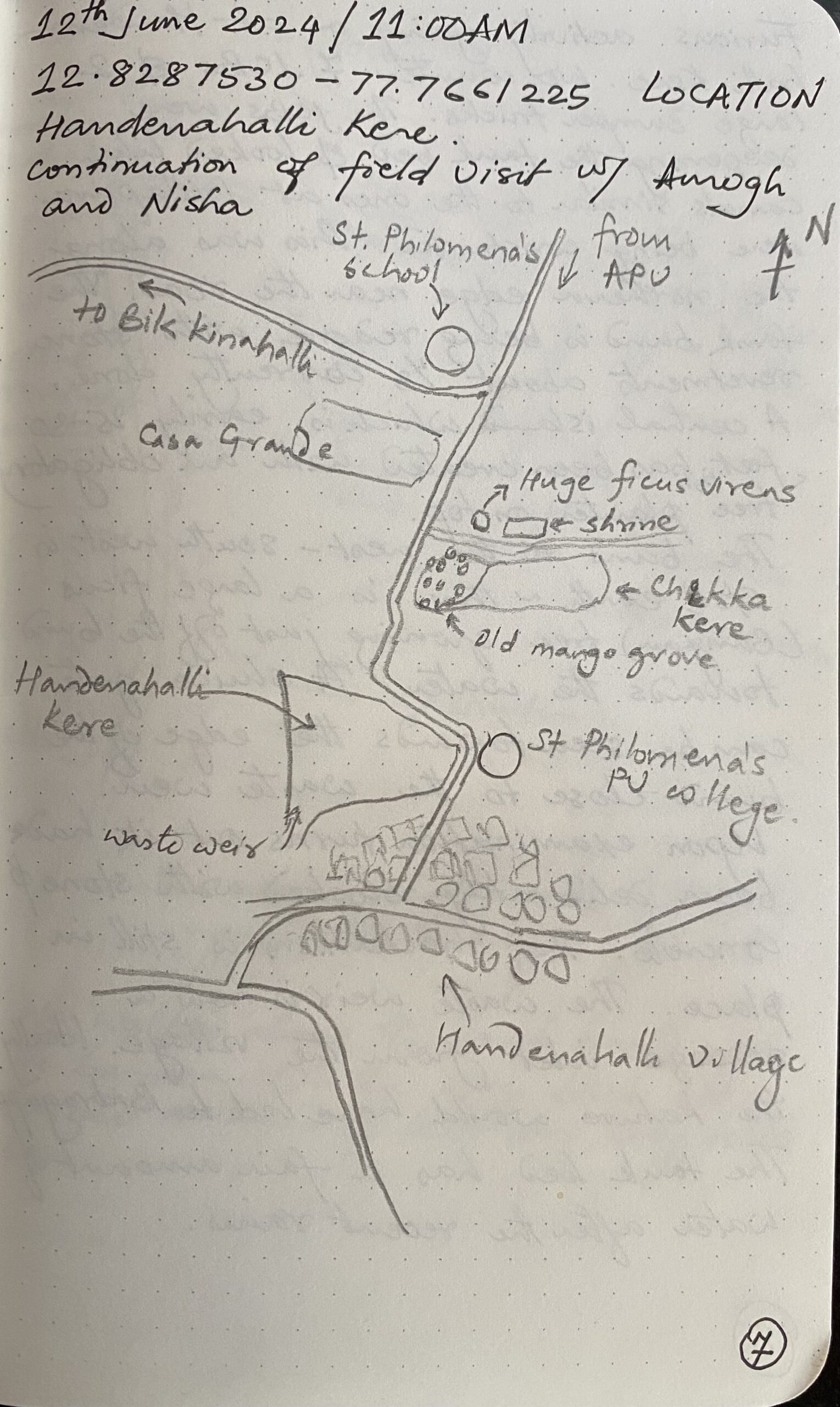

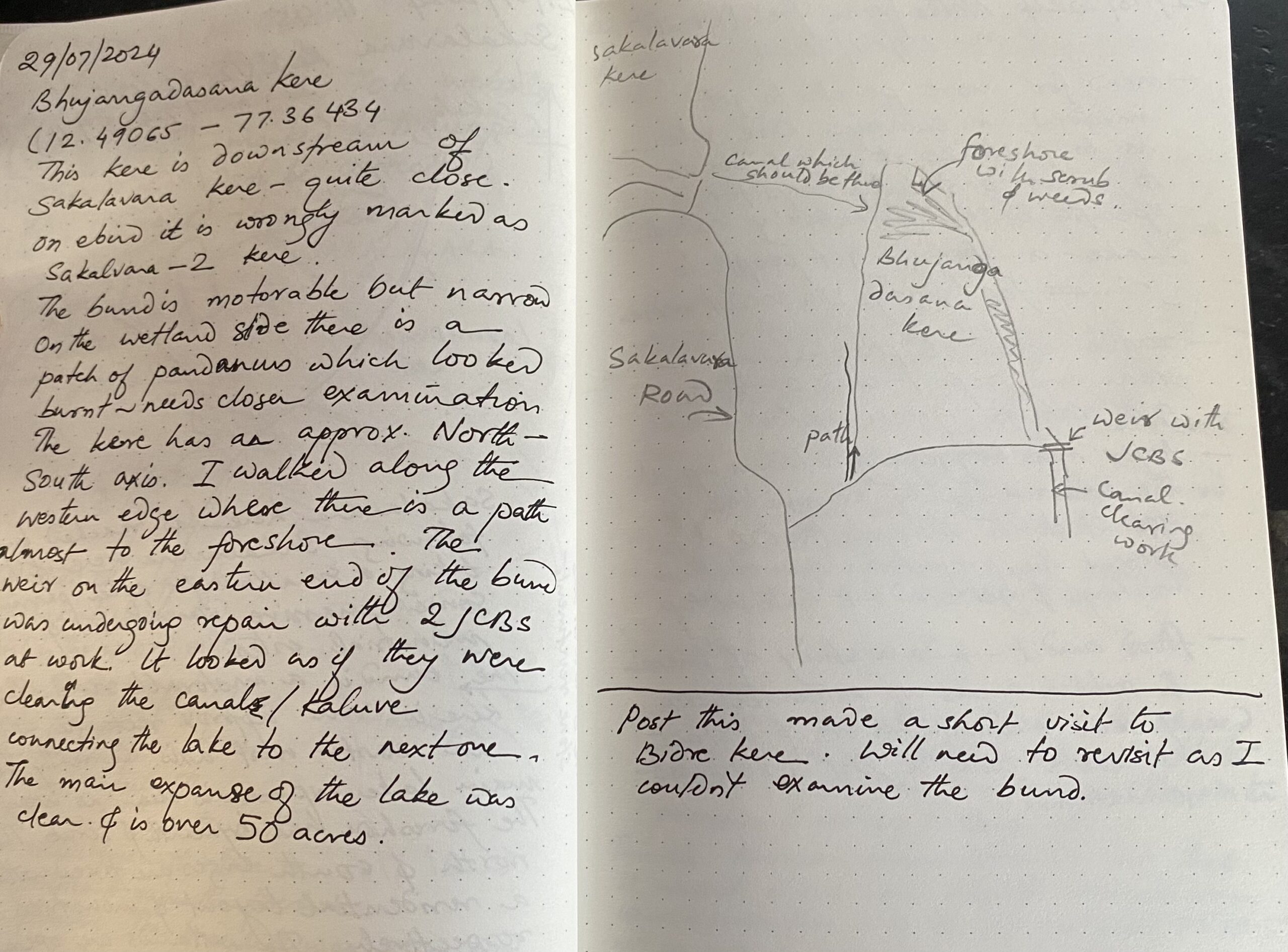

Examples of notes taken during field surveys of Billapura, Bhujangadasana and Bikkanahalli keres.

The figure above shows examples of notes taken during surveys of three tanks just off Sarjapur Road and are part of the same lake system.

Field surveys are also an important educational tool when we take students to the field. They are a low impact way for students to understand the field, learn observation and documentation skills and relate what they read to what they see on the land.

So if you are interested in understanding your locality head out with a notebook, keep your eyes open and start writing.