July 2023

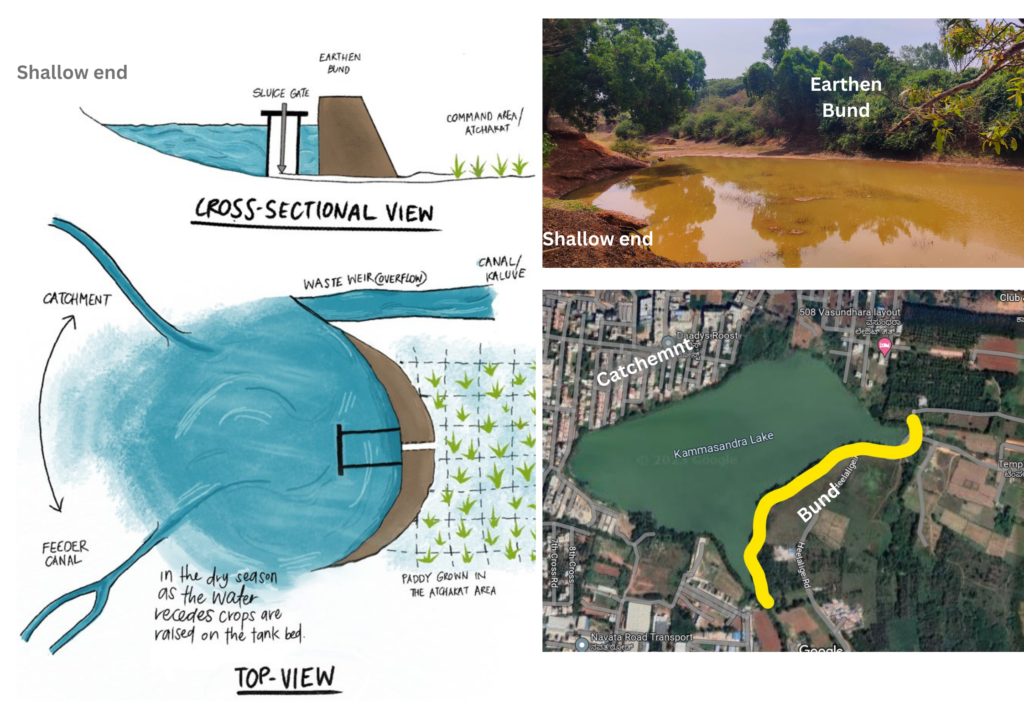

It is interesting to think about what the words tank and lake connote. A tank or kere architecturally consists of an earthen bund built to block water across a low valley. The water overflow is fed via weirs (kodi) into other tanks further below in the topography. A sluice gate controls the flow of water into the irrigated area behind the tank bund. In some sense, tanks belong to the past, an agricultural landscape where life was seasonally arranged and revolved around the rains. Tanks followed these seasons, with water receding in the dry months and the tank filling up and overflowing in the wet.

Architects Anuradha Mathur and Dilip Da Cunha describe it in their book Deccan Traverses as, “The series and parallels of Bangalore’s keres operate between two ends of a clay economy: a dry bed that provides the material for Ganapathi idols, and the full tank that allows for the immersion of these idols following the rains”.

More prosaically, tanks followed the seasonal calendar with desilting and maintenance activities being done as the rain waters receded. The exposed portion of the tank bed was used to raise dry land crops such as millets. In the monsoon, the irrigated lands behind the tank bund (called the atchakat) were used for raising paddy by allowing water to flow through the sluice gate into these fields. Water distribution was controlled by neergantis, who had knowledge of the geography and timetable to be followed when watering fields. (The many negotiations that decided this watering schedule are documented by Esha Shah in her book which we have linked in the resources). Tanks were thus integrated into the agricultural landscape and indeed were the linchpin of village life and economy.

A lake in the South Indian context is the modern version of the tank. A tank morphs into a lake as an area urbanizes. As the land use pattern changes and agricultural fields get converted into residential layouts or offices and industries, the older uses of a tank are no longer relevant. No longer is there a need for a diffuse boundary between a tank and paddy or ragi fields. The transition zone with a wetland is also deemed un-necessary as land becomes too precious to be ‘wasted’. It then tends to get filled in and reclaimed (never mind that this region will be the first to flood during the monsoon season).

A lake is set in an urban or peri-urban landscape and has a defined boundary. The most favoured model for a lake is the soup bowl design implemented across lakes in Bengaluru. The lake boundary is defined with a stone wall or revetment, typically with a central island as a beautifying element, it essentially looks like a large swimming pool. The city administration strives to give a lake a ‘neat’ look, with a hedge along the fenced cobbled walkway and standard trees and shrubs planted at the entrance. It is a far cry from the ‘wild’ aspect of a tank, with its diffuse borders, mud paths and many trees.

A tank that is in the process of being converted into a lake. Note the classic soup bowl design, with a fixed boundary (stone revetment) all around and a central island. This is Konanakunte lake, near Yelachenahalli Metro Station, off Kanakapura Road.

The connections of the tank system via kaluves (canals) are also lost with each lake becoming an isolated water body as a lake is fully bordered with stone. Indeed there are a few hundred ghost lakes within Bengaluru city limits, tanks that got converted to lakes and which subsequently were encroached and built over.

The uses a lake is put to are now different because it serves a different constituency. The biggest use of the lake is for recreational purposes – it becomes a place for people to come into contact with nature in a largely built-up and concretized landscape, so a lake has lots of walkers, joggers, photographers and bird-watchers. People also use it as a place to relax and escape from the busyness of the city – although typically the BBMP frowns upon people who ‘loaf’ around in public places, especially couples.

Lakes in Bangalore city are also used for certain traditional occupations. Fishing is still a lucrative activity practised in many city lakes. Fishing rights are sold by the BBMP (or any other state agency that is the lake custodian) to contractors who then hire fishermen to stock the lake with fishlings. The fisherman harvest their catch after it grows to the right size earning good money. Perhaps fish grow faster in the city’s lakes given the high level of nutrients (i.e. sewage) in the water? Lakes that are away from the city centre and more ‘wild’ are also used for growing and harvesting various kinds of soppu, serving as an important source of nutrition for the poor. So lakes are still a source of livelihood for many different people – a subject that needs to be studied better to understand their full benefits.

Thus while a lake is only a poor cousin of a tank, it still serves many important purposes from flood control, providing access to nature for a large cross-section of people, to maintaining livelihoods. Therefore we say ‘Better Lake Than Never’ making the case that these water bodies need to be protected even when their original purpose has changed completely. Now go to your local water body and determine whether it is still a tank or a lake.